to get out of the US Army.

Jimi Hendrix might have stayed in the army. He might have been sent to Vietnam. Instead, he pretended he was gay.

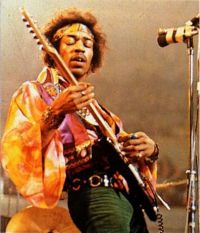

And with that, he was discharged from the 101st Airborne in 1962, launching a musical career that would redefine the guitar, leave other rock heroes of the day speechless and culminate with his headlining performance of The Star-Spangled Banner at Woodstock in 1969.

Hendrix’s subterfuge, contained in his military medical records, is revealed for the first time in Charles Cross’ new biography, Room Full of Mirrors.

Publicly, Hendrix always claimed he was discharged after breaking his ankle on a parachute jump, but his medical records do not mention such an injury.

In regular visits to the base psychiatrist at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in spring 1962, Hendrix complained that he was in love with one of his squad mates and that he had become addicted to masturbating, Cross writes. Finally, Captain John Halbert recommended him for discharge, citing his “homosexual tendencies” — four years before Arlo Guthrie suggested that path for avoiding military service in the protest song Alice’s Restaurant.

Hendrix’s legendary appetite for women negates the notion that he might have been gay, Cross writes. Nor, Cross says, was his stunt politically motivated: Contrary to his later image, Hendrix was an avowed anti-communist who exhibited little unease about the escalating US role in Vietnam.

He just wanted to escape the army to play music — he had enlisted to avoid jail time after being repeatedly arrested in stolen cars in Seattle, his hometown.

Room Full of Mirrors, titled after an unreleased Hendrix tune, is being published this summer to coincide with the 35th anniversary of his September 18, 1970, death from a sleeping-pill overdose. It is Cross’ second biography of a popular musician who died at age 27; Heavier Than Heaven, a 2001 bio of Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, was a New York Times best seller.

The new bio is culled from nearly four years of research, including access to Hendrix’s letters and diaries, along with military records provided by a collector the author won’t name.

Cross focuses on Hendrix’s complex personal life and psyche more than his music.

It’s not how much I know about Jimi’s B-sides; it’s how much I know about the emotional arc of his life,

Cross said in an interview.

The portrait that emerges is similar, in many ways, to that of Cobain. Both men grew up in poverty in Washington state, dreamed from an early age of becoming rock stars, found themselves with more fame than they knew how to handle and eventually retreated into a haze of drug use.

Cross, who lives just north of Seattle, describes Hendrix’s troubled childhood. Jimi’s father, Al Hendrix, and mother, Lucille, both had drinking problems. Al, a landscaper, rarely found decent-paying jobs and frequently split with Lucille. Jimi and his siblings were often left by themselves, or in the care of family friends. Jimi eventually flunked out of high school.

Before Hendrix even owned a proper guitar, he played air guitar using a broom, then a beat-up hunk of wood with a single string.

When he was 16, his father bought him a right-handed electric guitar that Hendrix had to restring to play lefty.

Room Full of Mirrors is filled with nuggets: After a show in Seattle, he had a star-struck teenager drive him around his old haunts; he allegedly had an affair with French actress Brigitte Bardot, precipitated by a chance meeting at the Paris airport; promoters at Woodstock refused to let him play an acoustic guitar. (Cross doesn’t cite a source for the Bardot liaison, and says the actress didn’t respond to his attempts to contact her.)

After his discharge, Hendrix formed a band with former Army pal Buddy Cox and began touring Southern clubs on the “Chitlin’ Circuit.” During those years, from 1963-1965, Hendrix played to black audiences with the King Kasuals and as a backup to Solomon Burke, Otis Redding, Curtis Mayfield and Little Richard.

Unable to make a living in the States — primarily because of his colour — Hendrix went to England in 1966 and took London by storm with his now-polished blend of soul, blues and rock. Within eight days of his arrival, he floored guitar gods like Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck. Hendrix remained in London for nearly a year, forming the Jimi Hendrix Experience and releasing his first album.

On his way to the Monterrey Pop Festival in summer 1967, he was mistaken for a bellhop by a woman at the Chelsea Hotel during a layover in New York.

It was a cold reminder of his ethnicity, Cross writes.

Hendrix was always uneasy being one of the first black stars to attract a white audience; he wanted to be welcomed by blacks, too.

Following Woodstock, his friends tried to arrange a show for him at the Apollo in Harlem, where his friends teased him about his drug of choice — LSD — being a “white” drug. The legendary theatre refused, afraid the concert would draw too many whites

One Reply to “Jimi Hendrix pretended to be gay”